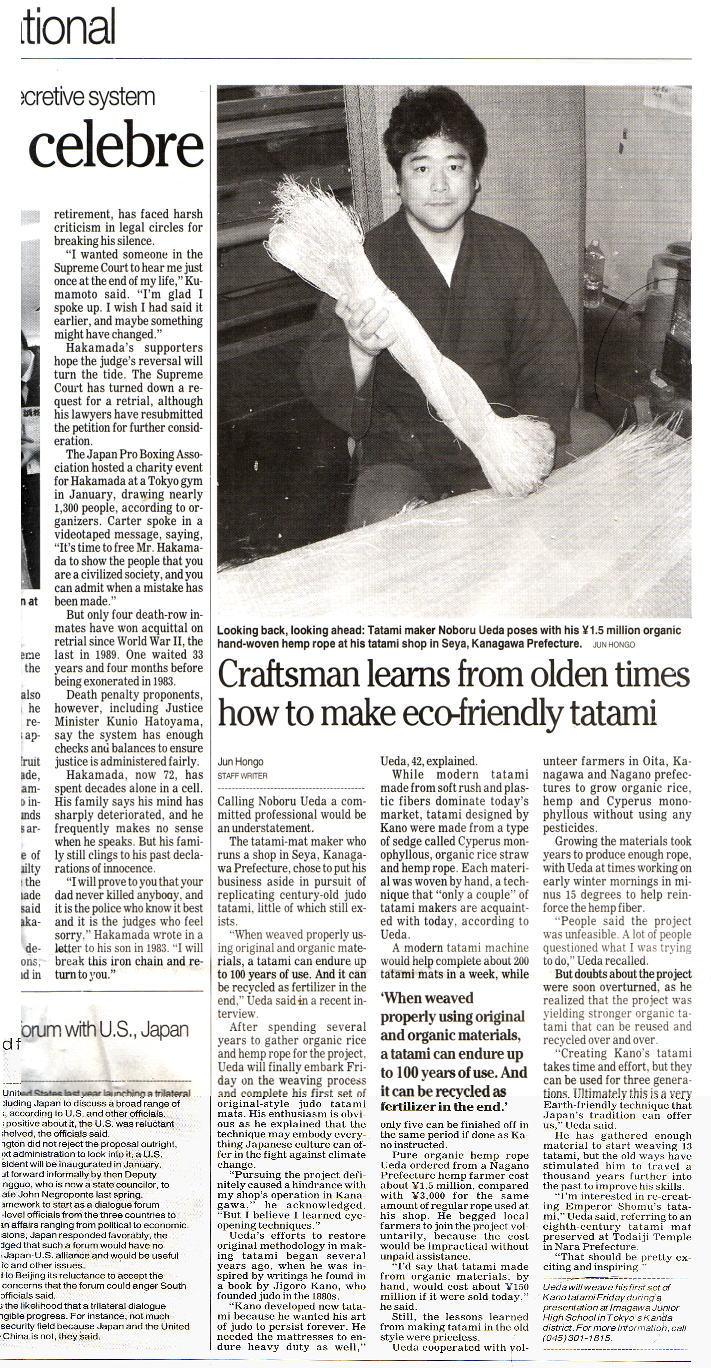

Calling Noboru Ueda a committed professional would be an understatement.

The tatami-mat maker who runs a shop in Seya, Kanagawa Prefecture, chose to put his business aside in pursuit of replicating century-old judo tatami, little of which still exists.

"When weaved properly using original and organic materials, a tatami can endure up to 100 years of use. And it can be recycled as fertilizer in the end," Ueda said in a recent interview.

After spending several years to gather organic rice and hemp rope for the project, Ueda will finally embark Friday on the weaving process and complete his first set of original-style judo tatami mats. His enthusiasm is obvious as he explained that the technique may embody everything Japanese culture can offer in the fight against climate change.

"Pursuing the project definitely caused a hindrance with my shop's operation in Kanagawa," he acknowledged. "But I believe I learned eye-opening techniques."

Ueda's efforts to restore original methodology in making tatami began several

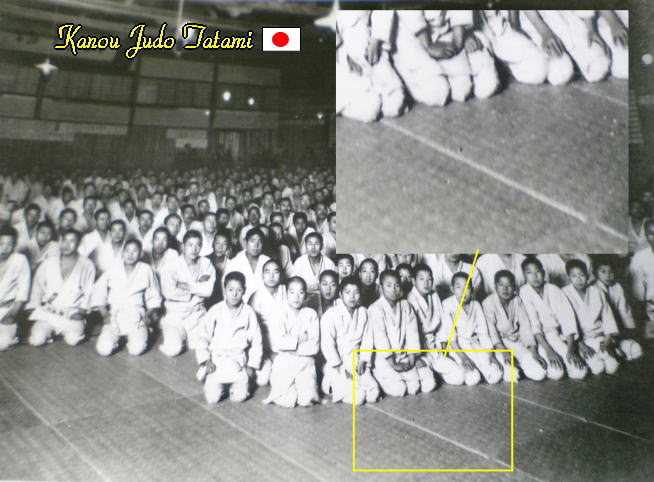

years ago, when he was inspired by writings he found in a book by Jigoro Kano, who founded judo in the 1880s.

who founded judo in the 1880s.

"Kano developed new tatami because he wanted his art of judo to persist forever. He needed the mattresses to endure heavy duty as well," Ueda, 42, explained.

While modern tatami made from soft rush and plastic fibers dominate today's market, tatami designed by Kano were made from a type of sedge called Cyperus monophyllous, organic rice straw and hemp rope. Each material was woven by hand, a technique that "only a couple" of tatami makers are acquainted with today, according to Ueda.

A modern tatami machine would help complete about 200 tatami mats in a week, while only five can be finished off in the same period if done as Kano instructed.

Pure organic hemp rope Ueda ordered from a Nagano Prefecture hemp farmer cost about ¥1.5 million, compared with ¥3,000 for the same amount of regular rope used at his shop. He begged local farmers to join the project voluntarily, because the cost would be impractical without unpaid assistance.

"I'd say that tatami made from organic materials, by hand, would cost about ¥150 million if it were sold today," he said.

Still, the lessons learned from making tatami in the old style were priceless.

Ueda cooperated with volunteer farmers in Oita, Kanagawa and Nagano prefectures to grow organic rice, hemp and Cyperus monophyllous without using any pesticides.

Growing the materials took years to produce enough rope, with Ueda at times working on early winter mornings in minus 15 degrees to help reinforce the hemp fiber.

"People said the project was unfeasible. A lot of people questioned what I was trying to do," Ueda recalled.

But doubts about the project were soon overturned, as he realized that the project was yielding stronger organic tatami that can be reused and recycled over and over.

"Creating Kano's tatami takes time and effort, but they can be used for three generations. Ultimately this is a very Earth-friendly technique that Japan's tradition can offer us," Ueda said.

He has gathered enough material to start weaving 13 tatami, but the old ways have stimulated him to travel a thousand years further into the past to improve his skills.

"I'm interested in re-creating Emperor Shomu's tatami," Ueda said, referring to an eighth-century tatami mat preserved at Todaiji Temple in Nara Prefecture.

"That should be pretty exciting and inspiring."